Topics for today

- Inheritance

- The Cascade

- Shorthands

- DRY

- Custom properties for cascading variables

p,

em,

mark

elements have the same font family, font size, and color that we set on their ancestor,

body

body? Does it get inherited too?

background

font

border

text-decoration

display

color

padding

white-space

margin

text-shadow

box-shadow

box-sizing

outline

--*

Inherited Not inherited

border: inherit;

font-size: initial;

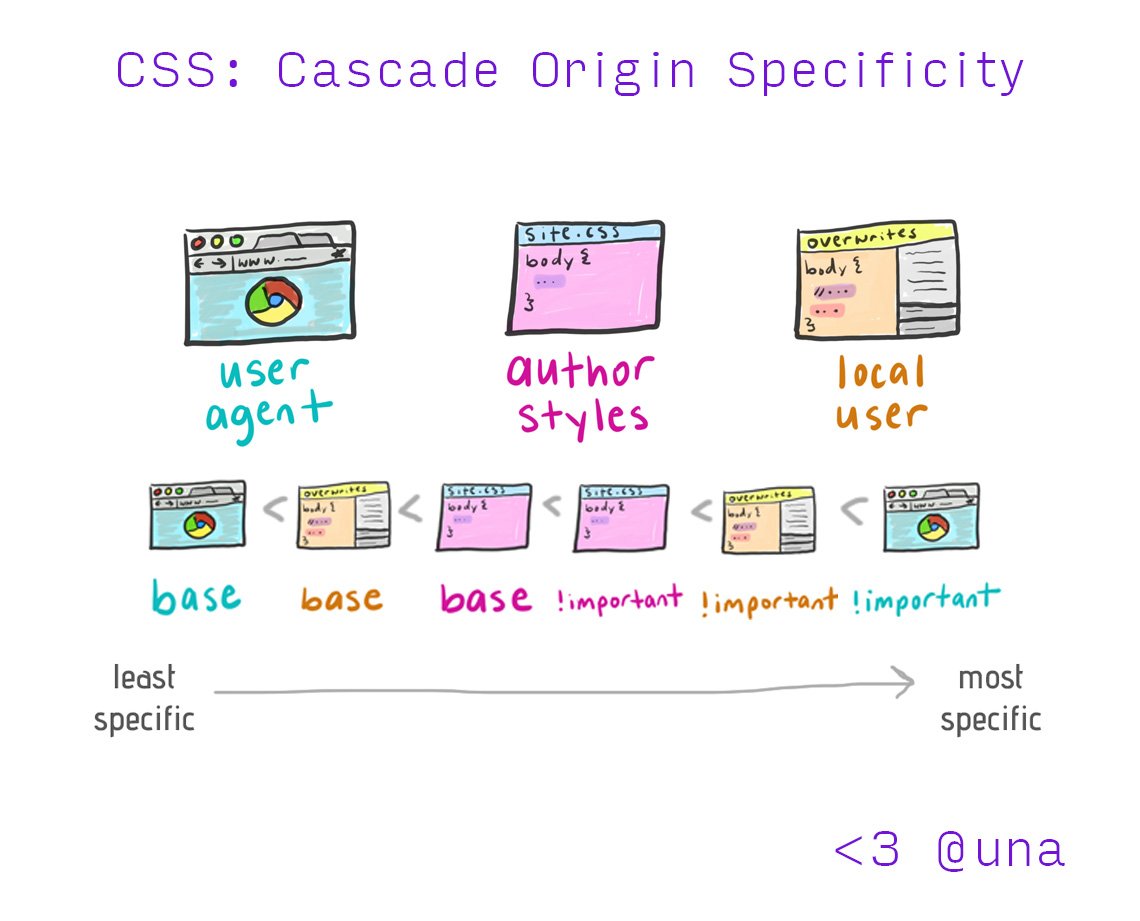

The algorithm that defines how to resolve conflicts.

h1#title {

color: red;

}

* {

color: blue !important;

}

!important?@scope is involved)@layer is involved)

body {

background: yellow;

}

body {

background: pink !important;

}

button {

border: none;

}

button {

border: 2px outset #777;

}

button {

border: none;

}

button {

border: 2px outset #777 !important;

}

(Unless !important is involved)

#id selectors.classes, :pseudo-classes, [attributes](1, 0, 0) > (0, 100000000, 100000000)

| Selector | Specificity |

|---|---|

style="background: red" |

(∞, ∞, ∞) |

:not(em, strong#foo) |

(1, 0, 1) |

:is(em, #foo) |

(1, 0, 0) |

:where(em, #foo) |

(0, 0, 0) |

.foo.foo.foo:not(#nonexistent)#foo to [id="foo"]:where()* Implicit inheritance, not via the inherit keyword!

!important inverts this)!important?border: .3em dotted steelblue;border: dotted .3em steelblue;border: steelblue .3em dotted;What happens if we swap the order of these two declarations? Why??

padding: .2em .5em .1em .5em;background: url(foo.png) 50% 50% / 100% auto no-repeat gold;background: gold no-repeat 50% 50% / 100% auto url(foo.png);font: 120%/1.5 Helvetica Neue, sans-serif;

background: url(cat.jpg)

0 10% / 100% 100%

no-repeat

content-box border-box

fixed;

background-image: url(cat.jpg);

background-position: 0 10%;

background-size: 100% 100%;

background-repeat: no-repeat;

background-origin: content-box;

background-clip: border-box;

background-attachment: fixed;

Every piece of knowledge must have a single, unambiguous, authoritative representation within a systemThe Pragmatic Programmer, Andy Hunt and Dave Thomas

def right_triangle_perimeter(a, b, c):

return a + b + c

# ... later on

p = right_triangle_perimeter(3, 4, 5)

from math import sqrt

def right_triangle_perimeter(a, b):

return a + b + sqrt(a**2 + b**2)

# ... later on

p = right_triangle_perimeter(3, 4)

.red-button {

background: hsl(0, 80%, 90%);

}

.primary-button {

background: hsl(0, 80%, 90%);

}

button {

border-radius: 5px;

padding: 5px 12px 6px;

font-size: 24px;

line-height: 24px;

}

button.large { font-size: 46px; }

button {

border-radius: .2em;

padding: .2em .5em .25em;

font-size: 100%;

line-height: 1;

}

button.large { font-size: 200%; }

.tab {

border-radius: .3em .3em 0 0;

padding: .1em .5em .1em .5em;

margin: 0 .1em 0 .1em;

}

.tab {

border-radius: .3em;

border-bottom-left-radius: 0;

border-bottom-right-radius: 0;

padding: .1em .5em;

margin: 0 .1em;

}

Three strikes and you refactor

Duplication is far cheaper than the wrong abstractionSandy Metz

-- and behave like normal CSS properties.var() function and we can use that anywhere (including inside calc()), except inside url().